--- Cleft Lip and Cleft Palate Update

The possibility that their child might be born with an anatomic malformation remains to be one of the most common worries of expectant parents. A rich interplay of random genetic and environmental factors play major roles in the development of anatomic malformations.

Among the anatomic malformations, cleft lip with or without cleft palate, is certainly one of the most common birth defects observed. At one point or another, you must have encountered someone who is bingot (that's the term we use in Batangas) and who speaks like a ngongo (pertains to the garbled nasal intonation of cleft lip/palate patients). Just like any handicap, it is sad sometimes when said deformities are made as objects of jokes and amusement among those who don't know any better. How many times has our local cinema made this as a subject of their comedy stunts?

The incidence of cleft lip with or without cleft palate varies among ethnic groups:

- Native Americans or Amerindians - 3.6 per 1,000 live births

- Asians - 2.0 per 1,000 live births, with the Philippines having it at 1.94 per 1,000 live births

- Indians - 1.5 per 1,000 live births

- European ancestry - 1.0 per 1,000 live births

- Africans - 0.3 per 1,000 live births

What causes cleft lip with or without cleft palate?

In this day and age, little is still known as to the specific cause of this condition. The usual medical answer will be the one I gave above which is genetic.

From 4 to 12 weeks of gestation (first 3 months of pregnancy), the upper lip and palate develop from tissues lying on either side of the tongue. As the face and skull are of the baby are formed, these tissues should grow towards each other and join up in the middle. When the tissues that form the upper lip fail to join up in the middle of the face, a gap occurs in the lip. if a single gap occurs below one or other nostril, it is termed a unilateral cleft lip, and when there are two gaps in the upper lip, each below a nostril, it is called a bilateral cleft lip, as shown in the picture below.

In cleft palates, the palate fails to join up and a gap is left in the roof of the mouth up into the nose.

This failure of the "joining-up process" is attributable to a genetic factor often traced in the child's family history. The latest issue of the New England Journal of Medicine carries an excellent medical study on a specific mutation of genes involved in the autosomal dominant form of cleft lip and palate, also known as Van der Woude's syndrome. The researchers were able to identify the gene that encodes for interferon regulatory factor6, also called IRF6.

Rather than bore you with fancy medical details, it is enough for you to know that their study is significant because this presents us with the possibility of predicting whether some parents are more likely than others to have a second child with the "isolated" form of cleft lip and palate (Van der Woude's Syndrome). Through genetic counselling, it will now be possible to surgically treat possible cleft lip and cleft palate patients at an earlier stage.

Certain types of drugs like phenytoin and sodium valproate (anticonvulsants), benzodiazepines like diazepam, and corticosteroids have been associated and may increase the risk of cleft lip and cleft palate incidence, especially if said medications were taken during the first 3 months of pregnancy. As always, this emphasizes once more the importance of consulting your respective obstetricians when you are pregnant.

Diagnostically, a cleft in the fetal lip may be visualized with the use of transvaginal ultrasonography as early as 11 weeks of gestation or the 3rd month of pregnacy and by means of transabdominal ultrasonography as early as 16 weeks or the 4th month of pregnancy. The graphic below courtesy of Dr. Beryl Benacerraf and the New England Journal of Medicine illustrates this:

In the weekly Perspectives of the NEJM, Dr.John B. Mulliken of Boston notes that humanitarian surgical missions from wealthy countries like Interplast, Operation Smile, and the Smile Train are "the objects of both praise and derision."

Praise, I can relate to but when he mentioned "derision," I was amazed as to why. Like most, I thought these surgical missions are considered heroes and saviors in whatever part of the country they go to --- be it Cebu, Davao, Bacolod, or right here in my very neigborhood of Metro Manila. He explained his reason:

"Many of these missions emphasize head counts --- the number of clefts repaired per trip. Often, there is little effort to involve local surgeons, who are left to manage postoperative problems once the visitors have departed. Some physicians in the host countries consider these expeditions to be "surgical safaris." Usually, there is NO continuity of care. These children need help with speech, dental and orthodontic services, and often secondary surgical procedures, and they must be followed until their facial growth is complete.I agree with him.

Many of these humanitarian organizations are currently in transition. It is no longer acceptable to send a team composed of junior residents or practicing plastic surgeons who are not actively involved in cleft care at home. There has been a major shift toward educating the local cleft-care teams, either through direct supervision or by financing visits to cleft-care centers in the United States. This change in philosophy led to the establishment of the Smile Train (headquartered in New York), and now a few other groups are coming on board with the same concept." [NEJM]

Even in surgical missions, the concept of don't-just-give-them-fish-but-teach-them-how-to-fish is still best.

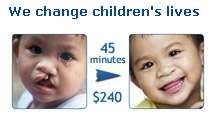

Lastly, I saw the picture below in one of the humanitarian organizations' website, and I am glad to note that even with the difficulties brought about by the cleft lip and cleft palate deformities to parents and children alike, the possibility of making these patients happy and be able to smile again is no longer that remote.

0 reactions:

Post a Comment